What Iíve built is the machine Iím using to write this monthís column - an LNW-80, built from a kit. Actually, LNW Research is hedging a little, calling these things semi-kits, since the units are nothing like a classic Heathkit (the standard of comparison) in either the ease of construction, the com- pleteness of documentation, instruc- tions, or parts.

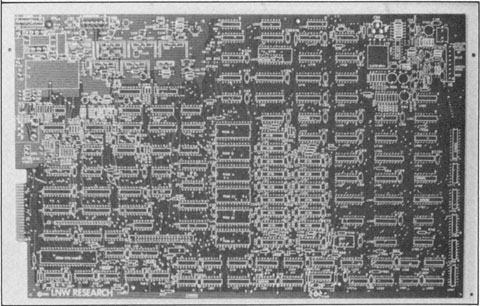

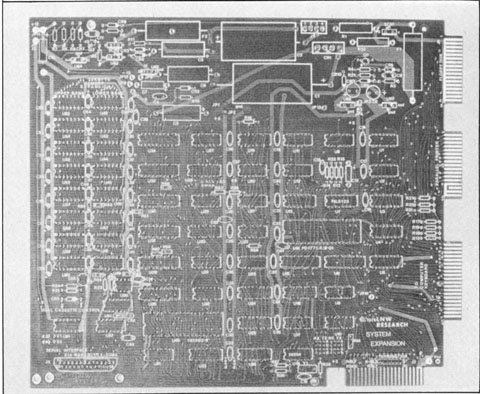

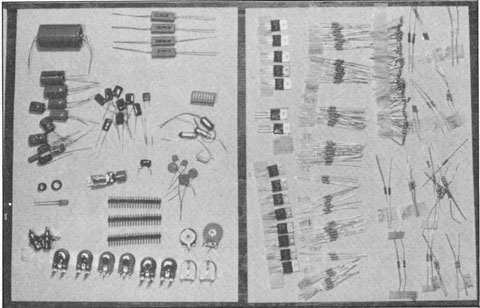

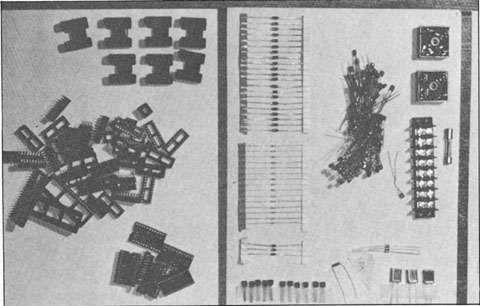

I selected the full-blown semi-kit: printed circuit boards for the CPU sec- tion and an expansion interface ($90 and $85 with gold edge connectors), keyboard with numeric pad ($100), metal case ($85), three hard-to-find parts kits ($140 - more on that later), and a Level II ROM set ($120). The semi-kit total, with shipping, was about $640. To that total I had to add the ex- pense of a bucketful of my own parts and quite a few purchases, including capacitors, resistors, integrated circuits (48K of memory, too), regulators, diodes, transistors, sockets, and miscellaneous whatsises like fuse cases and wire clamps - the kind of stuff I always thought I had in my oversized junkbox, but when it came down to needing it, the cupboard was bare. This investment came to about $250 more, making the total kit cost about $900. This is at least $700 below an assembled LNW-80 ($1,600), or about the same as a TRS-80 Model III purchased at discount.

Before jumping in with the construc- tion, you might want to know what this LNW computer is. The manufacturer calls it a Model I/III-compatible micro- computer with added features. But the LNW-80 is both more and less than that. Model I/III users will find it very familiar, while first-time computer users will appreciate the wide range of features that TRS-80 owners have known for some time. But Iíll hold off listing these capabilities until I describe the assembly and operation of the computer. For the moment, consider that this machine contains just about every feature Model

LNW-80 kit

a worthwhile

endeavor

I owners have hoped for or modified their units to contain, and many of those the Model III should have had. In addition, high-resolution graphics (384 by 192) and color are standard.

In the next two columns, Iíll cover assembly and operation, plus some fixes, to the LNW-80. In addition to running through the assembly of the machine, I will also present a few quick and easy modifications that will facil- itate using some of the LNWís special features.

Before I begin, readers, please take note: Iím going to sound harsh in some of my criticisms of LNW Research, their documentation and support, and some aspects of the computer itself. Nevertheless, I purchased the LNW be- cause I had the opportunity to use one

Opening the Box

The first surprise is how heavy the delivered box is - $11.17 worth of UPS up here to New England. Although most of the weight turns out to be the heavy metal case, that heftiness gave me a reassuring feeling about the whole system. Iím always a sucker for appearances, but this hunch was a good one. The case is 1/16-inch solid steel, painted cream white, and packed in plenty of scratch protection. A few bags of screws dropped out, and un- derneath was a pair of printed circuit boards.

All the integrated circuits - the so- called hard-to-find parts kit - were thrown ignominiously into a plastic bag, with the static-sensitive ones bundled into little aluminum foil globs. The five-pound transformer had fortunately been packed well and pre- vented from crushing the other parts. The keyboard is complete and also well packed; the connector survived un-

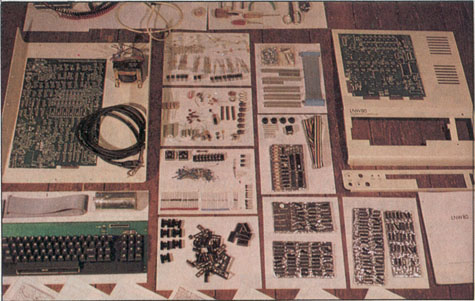

Photo l. All the parts assembled for a complete

LNW-80 kit. Clockwise from back: necessary tools;

case top and expansion PC board; case back; manuals;

foil trays of integrated circuits; sockets and

heat sinks; keyboard, cable, and power-supply capacitors;

main PC board, cord, transformer, in case

bottom; at center are remaining small parts and hardware;

at very bottom (just visible) are sche-

matic sheets.